The Fight-or-Flight Response: How Your Body Reacts to Stress

Imagine you're walking alone in a dark alley, and suddenly, you hear a strange noise behind you. Your heart starts pounding, your breathing becomes rapid, and your muscles tense up. What's happening to your body? This is the fight-or-flight response, a natural reaction that kicks in when we face threatening or stressful situations. Let's dive into what exactly happens during this response and how it affects us.

The Brain's Role: The Amygdala and Hypothalamus

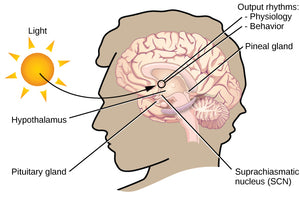

When we encounter a threat, our brain's alarm system, known as the amygdala, springs into action. The amygdala is responsible for associating sensory signals (like what we see, hear, or smell) with emotions such as fear or anger. It then sends a distress signal to the hypothalamus, which acts as the command center of the brain, communicating with the rest of the body through the sympathetic nervous system.

The Fight-or-Flight Response to Acute Stressors

Once the sympathetic nervous system is triggered, it sets off a series of changes in the body to prepare us for fight or flight. It sends a signal to the adrenal medulla, a part of the adrenal glands located on top of our kidneys. The adrenal medulla responds by releasing adrenaline, a hormone that surges into our bloodstream.

Adrenaline's Impact

Adrenaline is like a superhero hormone that causes several physiological changes in our body. It makes our heart beat faster, pumping blood to our muscles, heart, and vital organs. This increase in blood flow raises our blood pressure. Our breathing becomes rapid to take in as much oxygen as possible. Adrenaline also prompts the release of glucose (blood sugar) and fats into our bloodstream, providing energy for the fight-or-flight response.

The Parasympathetic Nervous System: Restoring Balance

Once the threat is gone, the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system steps in to calm down the stress response. While the sympathetic branch accelerates our heartbeat and increases blood pressure, the parasympathetic branch slows down our heartbeat and reduces blood pressure. It also allows our digestion to resume, which is usually inhibited during the fight-or-flight response.

The Fight-or-Flight Response to Chronic Stressors

Sometimes, our brain continues to perceive a situation as threatening even after the initial surge of adrenaline subsides. In such cases, the hypothalamus activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. This system involves the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal glands working together to keep the stress response going.

The HPA Axis

The HPA axis relies on hormonal signals to sustain the stress response. When the hypothalamus senses ongoing threat, it releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) into the bloodstream. CRH then stimulates the pituitary gland to produce and release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH travels through the bloodstream and reaches the adrenal glands, stimulating the release of stress-related hormones, including cortisol.

Cortisol's Effects

Cortisol, often referred to as the stress hormone, plays a crucial role in the fight-or-flight response. It provides a quick burst of energy and lowers our sensitivity to pain, which can be beneficial in certain situations. However, excessive cortisol levels can impair cognitive performance and weaken the immune response, making us more susceptible to stress-related illnesses.

Maintaining Balance: Feedback Mechanism

Fortunately, our body has an efficient self-regulation system. Both the hypothalamus and pituitary gland have receptors that monitor circulating cortisol levels. If cortisol levels rise above normal, these receptors trigger a reduction in CRH and ACTH production, bringing cortisol levels back to normal.

Looking Beyond Fight or Flight: The Freeze Response

While the fight-or-flight response is commonly known, it doesn't tell the whole story. According to researcher Gray, animals, including humans, typically display a freeze response before fighting or fleeing. This initial freeze response acts as a stop, look, and listen phase, making us hyper-vigilant to detect any signs of danger. It helps us gather information to determine the most appropriate response to a threat.

Positive Alternatives: Tend and Befriend

It's often assumed that men respond with fight or flight, while women are more prone to tend and befriend. However, a study by Von Dawans and colleagues challenged this view. They found that acute stress can lead to greater cooperative and friendly behavior in both men and women. Human beings are inherently social animals, and during times of crisis, stress can bring people together, fostering cooperation and support.

Genetic Basis for Sex Differences

Research by Lee and Harley suggests that gender differences in the fight-or-flight response have a genetic basis. The presence of the SRY gene on the male Y chromosome promotes aggression and the classic fight-or-flight response to stress. Females, lacking the SRY gene, may exhibit tend and befriend behaviors instead of fight or flight.

The Negative Consequences of the Fight-or-Flight Response

While the physiological responses of fight or flight may be adaptive for immediate threats, modern stressors often don't require such physical activity. Repeated activation of the stress response can have negative consequences. For example, increased blood pressure associated with the sympathetic nervous system activation can lead to cardiovascular problems. Additionally, excessive cortisol can suppress the immune system, increasing the likelihood of stress-related illnesses.

Conclusion: Understanding Your Body's Response to Stress

Learning about the fight-or-flight response provides valuable insights into how our bodies react to stress. While it is a natural and adaptive mechanism, it's essential to recognize the potential negative consequences of chronic stress and find healthy ways to manage it. Now that you have a better understanding of the fight-or-flight response, test your knowledge by taking our quiz and see how much you've learned!